.png)

This episode of Alicast takes you behind the scenes of Alibaba’s groundbreaking new Shanghai campus, a visionary project designed by the world-renowned architectural firm Foster + Partners. Known for iconic creations like Apple Park and the Gherkin, Foster + Partners has once again redefined workplace design, creating a space that blends transparency, innovation, sustainability, and community.

The guest host is Huang Jinglu, an architect who brings her expertise to uncover the story behind this extraordinary project. She is joined by Jeremy Kim and Yu Zheng, partners at Foster + Partners, who share their insights into the design and construction of this campus. Together, they explore how the bold vision of “See and Be Seen” inspired a design that breaks traditional office boundaries.

As Jeremy Kim aptly puts it, this campus is “designed to enhance collaboration, well-being, and innovation for generations to come.” Join us as we dive into the architectural, engineering, and cultural significance of Alibaba’s new Shanghai campus—a building that’s not just a workspace, but a statement about the future of work itself.

Enjoy!

Below is a transcript of this Alicast, edited for clarity and brevity

Jinglu:

Welcome to Alicast. I’m Jinglu. Today, we are diving into the story of Alibaba’s Shanghai campus, designed by world-famous architecture firm Foster and Partners. Joining us today are Jeremy Kim and Yu Zheng, partners at Foster and Partners. Together, we uncovered the story behind the design and construction of the new Alibaba campus in Shanghai.

Jeremy and Zheng, thank you so much for joining us from the London office today.

Jeremy Kim and Yu Zheng:

Thank you for hosting us.

Jinglu:

Let’s start with the vision for this project. We all know Alibaba is one of the most iconic tech companies in the world. What were the initial requirements from the client when you just received this job?

Jeremy:

Some people may know that the project came as a competition. Alibaba invited us, along with other architects, to come up with an idea that we thought was appropriate for this site. As you mentioned, it’s a very important site, and it was an important project for Alibaba. And there were very specific requirements by Alibaba to ensure that we meet their expectation.

This is going back many years. One of the most memorable brief or requirements was “See and be Seen”. So they wanted a building that could see and be seen. It’s not a common request from our client. And both Zheng and I, when we first met with the person who was leading the competition from Alibaba side when she mentioned the word “See and Be Seen”, we were quite taken by that. And it was quite an inspiring brief, I have to say, which led to many interesting architectural features of the building.

And I thought it was a wonderful story because it was not the architect who came up with everything, but the client who could inspire their architects with the brief.

The concept of “See and be Seen” is where it all started. The starting point was to design a building that Alibaba can see the public, but also a building through which the public can see Alibaba.

Yu Zheng:

Also to add on, I think that was a perfect moment for the city of Shanghai to establish the positioning of the area, which is the Xuhui Riverside area, which is based on converting the industrial heritage story into a more technology-led futuristic zone, so that in a way, the government was looking for a kind of showcase along that area as well, which made perfect sense for Alibaba to come in to purchase that land and to develop their own headquarter buildings there.

Jinglu:

I think it explains a lot of the concept and all the design results I’ve seen from the site. I recently visited the site, and honestly, what struck me the most was how it didn’t feel like the typical office buildings.

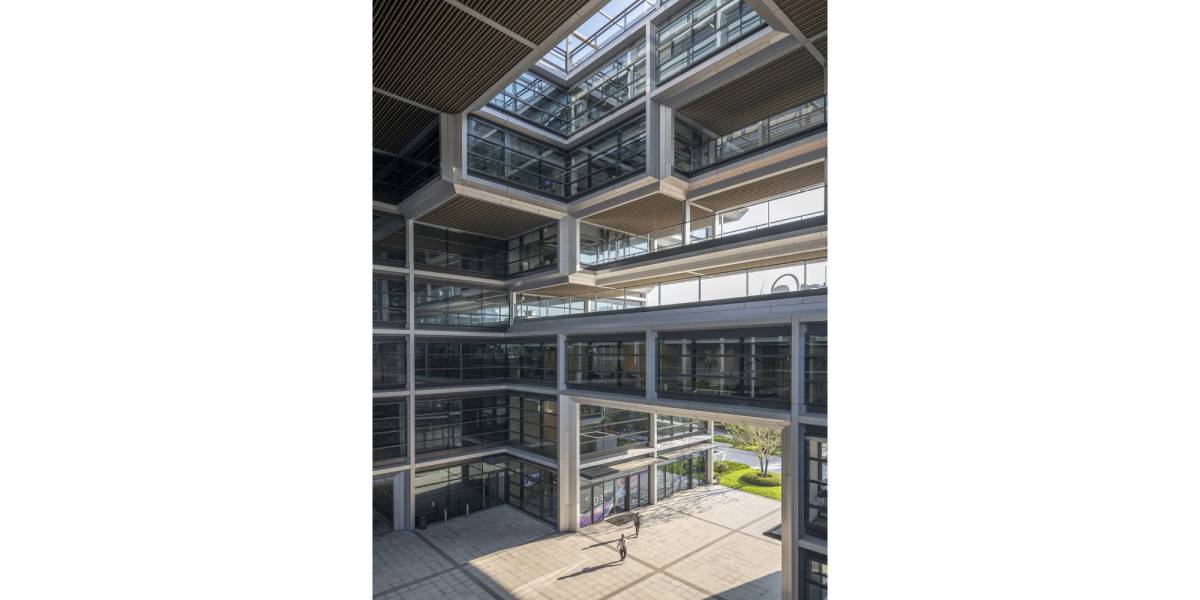

But this one is very different. It reminds me of a Lego structure. From the outside, it looks like a rectangular box, but with openings on the side, on the top, and a central atrium carved out from the box. It is such an unconventional design. When I first saw the renderings from the website, I was a little bit confused, and after I visited the site, I felt like it was related to the natural ventilation, the sunlight, and the views. Could you explain how it leads to this specific design we see today?

Jeremy Lim:

It also links back to the brief- “See and be Seen” – that’s where it all started. So the starting point was to design a building that Alibaba can see the public, but also a building through which the public can see Alibaba. So, the common denominator was to create a public space.

The general public can come and enjoy it, but normally, there’s a building, and then you allocate some space next to it and create a public space. That’s a very typical way of designing, right? I’m not saying that’s wrong. But because of this very specific and powerful brief, we felt that the building had to do more than that. In a way, the creation of public space shouldn’t just be some leftover space next to the building, but it needs to be somehow integrated into the building itself.

That’s easier said than done. How do you create a space, a place where the public can access it? That is in the heart of Alibaba. There are security issues. There are many different issues. You can’t let people walk into Alibaba’s operation, literally, that wouldn’t be a good idea. So we thought, okay, we will still create an open space. But if that open space was protected and surrounded by the building and that was a very interesting moment for the project.

So, ever since then, the design has become, in a way, very challenging and exciting. How do you create an open space within a building? We tried conventional ideas, conventional ways of design, and so on, but then this is where we decided to try “Genetic Algorithms“, using the power of the computer to see how, based on the input that we make, what sort of solution the machine would give us.

And this is where the design took a very dramatic turn. Since we asked the machine to consider environmental importance, consider ensuring the space is environmentally optimized. So you get the wind when you need it, but you don’t get the wind when you don’t need it. You need the same with the sun and the permeability, and you need to ensure that everybody in the building can enjoy the view because it’s almost madness not to enjoy the view if you’re on that site.

So these factors, along with the creation of a public space that’s well protected and a building that can “See and Be Seen,” and eventually, after a few generative processes, we were able to see a very interesting concept. That was the beginning of our conceptualization.

Jinglu:

You mentioned the computer generated some of the iterations. Do you have this kind of “genetic algorithm” that helps you generate a lot of different iterations to maximize the sunlight or to have better natural ventilation?

Yu Zheng:

I think the starting point is that a decision was made in a way that we would like to create a public space at the heart of the site that wasn’t coming from a computer. What was coming from computer process was, as you mentioned, once we set a goal, then we utilized the computer technology coming to help us, because otherwise, manually then that we would need to spend a lot of time looking at different options and come up with the optimal solution end of the day.

There are three key factors for us to consider in the process. There’s a view, as Jeremy mentioned, this is such an amazing location. That was part of the brief requirement to maximize the views of the river, the surrounding areas, and the CBD in the Putong area in the distance.

The second one is environmental factors, as you already mentioned. There’s a sunlight story, the wind story in winter and summer. How do you actually block the summer sun, introduce more winter sun into the public space, and so on and so forth?

Then the third one is really the area requirement, which fits in brief because, at the end of the day, we need to provide a working space for, I remember it’s 2, 000 people in total. So that comes with a certain area requirement.

Often, these three factors conflict with each other. The goal at that point was how we could efficiently and effectively find the right balance combining the three aspects of requirements, which is where the genetic algorithm comes to play in a really handy way because they can run fast, working out all the options and testing and evolving, and then come with a base model for us to start with, in terms of design process, if that makes sense.

Jinglu:

When I visited the site, some of the operation staff told me that their colleagues find the natural light on this campus is much better than in the Hangzhou headquarters, and they were very happy about that.

Also, the temperature in summer is six degrees cooler than the surrounding areas, which is significant. That is fantastic and very impressive. The operation team mentioned that the energy efficiency is significantly better than that of the neighborhood campus. So, I think your genetic algorithm design has achieved these results.

Jeremy:

That’s wonderful to hear.

Yu Zheng:

And maybe we could add on the point, for instance, on the environmental story. Normally, as you’re a designer or an architect and, of course, we all look at the design stages in terms of how the environmental impact could be dealt with and how sustainable buildings should be designed.

And what we did on this one, apart from the design stage, the algorithm, and all that coordination to make the building? Also, after the building was completed, we commissioned a thermal. What is it called?

Jeremy:

Thermal camera, thermal reading. So what we did was, as designers, we could only assume things with the best of our knowledge and expertise. But at the end of the day, you have to go back when the building is finished and see what you’ve assumed is actually being achieved. And that is a very nervous moment.

Yu Zheng:

When science comes to light.

Jeremy:

Yes, exactly. You can’t foresee this. No, nobody in the world can confirm that what I design, and my intent, will be delivered. Because that takes a lot of effort by not just yourself, but a team of people, working very hard to deliver together.

Anyway, with some nervousness, we commissioned a drone thermal reading. We wanted to measure the temperature, because Shanghai suffered some heatwave last summer, as you all know. On a very hot day, When the ground temperature was reaching almost over 60 degrees celsius, we commissioned a thermal camera to actually see what happens inside the building, in the public space, yeah?

So we measured the outside of Shanghai, then the same camera went inside the public space, and then we compared the temperature difference. The same applies to the surface and the air temperature. And the result was mind-blowing. That’s something we didn’t know. We could only design based on the knowledge and expertise to make sure the building will be cooler during the summer and warmer during the winter passively, not using energy or anything, just by the building itself.

We wanted to create this passive environment, passive benefit. That was the moment when we realized that it performs better. And it was hugely rewarding because this is what we wanted to do. And we can only thank everyone involved, including the client who supported and trusted us and delivered this together.

That’s the moment when we realized that it is really important and worth the effort to consider environmental benefits and make sure the building will perform passively right up front from the start of the design process.

Jinglu:

Do you have any sustainability consultant working with you, or could you share some of your thoughts on how you design for these extreme weather events or for resilience?

Jeremy:

We are one of those companies fortunate enough to have specialist engineers in-house. So, we work with our engineering team by default. And so during the competition stage, when we were establishing what should be considered, what’s important, and what passive measures should be introduced into the design. This was when our environmental team was involved.

Architects can only think, so far as to what based on common sense. If you want the building cooler during summer, you have to shade. And vice versa. If you want the building to be warm, you must start inviting sun during the winter. But then, engineers come on board and start giving us more specific guidelines. The weather these days is quite difficult to predict, there’s global warming, and we’re suffering more heatwaves during summer, and severe winter during winter, so we need to come up with measures that would use the least amount of energy, but for the building to be able to respond to these weathers differently during the winter and during the summer.

Yeah, working with engineers and specialists right from the beginning is very important because building, once it’s formed, becomes very difficult or more costly to make sustainable retrospectively. The best way to achieve a green building is right at the beginning where you choose your site, orientation, the height of the building, the things that people don’t really think about and might say, “Oh, is that really important for sustainability?”

I think that is the most important thing in sustainability. Once that is optimized, you will be in a hot climate, and you will want to minimize exposure to direct sun. Therefore, it affects the building’s orientation and massing, among other things. So, we should involve the engineers and work with those who know how to deal with climate challenges right from the beginning of the design process. And that’s one of the reasons why we’re very fortunate to have these specialist teams in-house and to be working with them on this project.

Jinglu:

I think another element that helps a lot with sustainability and well-being is the terraces. I find there is an abundance of terraces in these buildings. I visited some. The view was stunning. And the openings frame and the city skyline of Pudong CBD like an art piece to me. Also, the landscape design and art installations on the terraces are impressive. How did you approach the arrangement of these terraces?

Yu Zheng:

In a way, as part of the public story, i.e., making the building more public in that aspect, biophilia has been equally important, and it’s been highly recognized by the client’s team as well.

It’s not about providing 2000 desks for people to work, but about providing a home for them to be happy to work, because productivity would increase and attendance would increase, which means a lot.

We looked at all the latest headquarters buildings globally by leading organizations. One of those focuses has always been on how to keep the talent and the people, and making the staff happier by providing a nicer working environment plays a very important role in that, which comes with a reason and a requirement for the biophilia design.

As part of that, we fully utilize the location of the site, enjoying the views around, which becomes part of the story of why the massing, for instance, the top of the roof steps or terraces in the way that it does, which is to maximize the possibility of introducing outdoor working spaces: A is to fully utilize the outdoor working environment with views around, which is amazing, and B there was before the Covid hit the world in a way, after which there’s a lot discussion talking about, how do we work in that environment where you don’t want people to bundle together. Before that, it just happens to be that we’re already looking forward to the working environment. If you have more choices of working outdoors, then you decrease the density in essence and promote social distancing that works for that purpose. You carry on with the work you have to do. So that’s all kinds of combined considerations in the importance of the terraces and the platforms you have on the building.

And a note to say special thanks to the client’s team again because it was only during the design stage that we realized part of the open spaces were counted as part of the GFA of the building. So I think we took about 2000 square meters of the building.

Jeremy:

It’s 22 percent of the overall GFA.

You must know as an architect that a building can only be as good as its client. You can’t outdo your client.

Yu Zheng:

22 percent of the overall GFA is allocated to outdoor spaces. If you could imagine to any client, That’s unbelievable. It’s absolutely unbelievable.

Jeremy:

You must know because you’re an architect, you can’t sanction that as a client unless you really believe in the power of outdoor space. The space doesn’t have to be indoors for people to work. The work can happen outdoors, equally on the inside and the outside. And that, I think, the forward-thinking enabled us to create these terraces, and therefore, if you work in that building, you don’t even have to go upstairs or downstairs to enjoy the fresh air. Every floor in that building has outdoor space. That is something special I think you know, it’s not what every building has yeah And clearly, not every building allocates 22 percent of GFA as an outbound space.

We thank Alibaba for that, as we couldn’t have done it without that support. It’s impossible.

Jinglu: And this also creates a very different type of integration of public space and office space because, as I mentioned with Yu Zheng before, we really like the Kings Cross in London because that area is a very vibrant mixed-use area with office spaces integrated with open spaces of different scales.

It is still like an office building alongside a public space. But this time, it’s all integrated.

Jeremy:

That’s something that we want to celebrate in a way. This very inspiring brief led to a unique office building typology that we don’t see often elsewhere, yeah?

So I think it’s not just the building but it’s the modular of the building, the way you integrate public space within the an office HQ, not just speculative building, but this is Alibaba’s own building where they occupy and operate. The integration of public space within a very sensitive business setting is unique.

Normally, tech companies don’t want people to come near and see because they deal with sensitive information. They were thinking much grander than that, which led to this unique building prototype. So I think in that sense, it is something to celebrate.

Jinglu: Yeah. And I think the concept of “See and Be Seen” is carried throughout the process. I also noticed the multifunction hall on the seventh floor. It’s not a very traditional enclosed space with solid walls. It was enclosed by glasses. How do you design a hall with glasses on four sides?

Jeremy: So, again, this links back to the “See and Be Seen” concept, and I think it’s the confidence of Alibaba that they don’t need to hide themselves from the public. It’s the opposite. They want to engage with the public. They want the public to come and see how Alibaba operates, which led to these architectural solutions.

You must know as an architect that a building can only be as good as its client. You can’t outdo your client. Because without a client, there’s no need for that building, yeah? In that sense, the building and your design will only be as good as your client’s aspiration. When your client’s aspiration is big and it goes beyond the convention, then you will have a better chance of creating something that goes beyond the convention, right?

I think any special features, or “Wow moments” in that building, are because of the bigger visions established by Alibaba. So, I think, in that sense, we appreciate the client’s ambition and support. Because without this, we wouldn’t have been able to design this.

Yu Zheng:

“Transparency,” if you want to call it that way, I think in a way, the first one is going back to the environmental story that we talk about the sun and the wind; of course, another factor is the natural light. If you look at the plan of the building, we never have any part of the building over two spans in space.

So, over two spans of the structural spaces, you always either have a window, or you have an atrium, or you have a terrace. So that is to control the level of daylight you get, as well as the temperature, in the sense that you’re close to the outdoor spaces all the time.

And another layer that comes into play is that part of the brief was, of course, asking for event spaces. Again, the hall was one of them. But if you look at the whole building, there was a sunken courtyard, a ground floor, and an entrance square. There were different floors of platforms and terraces. They all become this whole system of event spaces. You can choose any if you want to launch products or hold small concerts.

That’s also part of the transparency in a way, again, as Jeremy mentioned, Alibaba is not afraid of showing something that the public can be able to, will be able to see it. You can host an event in the Sunken Courtyard or Ground Floor, which the public can access. Or visually, we can see something going on any of the terraces, which is part of the transparency story.

Okay, at the design stage, we didn’t think of it that way because they were designed for different purposes. But I think it’s an interesting way of summarizing if you want to call it transparency, in that sense. Yes, there will be glass, but there is more. There’s a deeper thinking behind that.

Jinglu:

It’s more of a metaphor for carrying from design to operation. Everything is carried with this idea. And as you mentioned the Sunken Plaza, I heard it has become a very popular spot for people. After lunch or dinner, they can go out of the canteen from B1 to the Sunken Plaza and have a short walk throughout the whole building. Also, the community of that district can borrow that area to host some of the community events. This also invites the public into this office campus.

Jeremy:

I think it’s wonderful to see. And thank you very much for sharing that, by the way, because we were there for the opening, but then we weren’t able to see how the building is actually being used.

So now it’s really encouraging to hear that the building is being used and loved by Alibaba and the community. That’s wonderful. That is truly wonderful.

Jinglu:

Also, as Zheng mentioned, the span and the structures, along with all those terraces, I can imagine the cantilevers bring a lot of challenges for structural engineering.

I also watched the video online that you lifted those cantilevers into the air and joined them together in the air. So, could you share some stories of the structural challenges and engineering achievements behind the scenes?

Yu Zheng:

From a design point of view, of course, once we settled on the principle of creating a public space at the heart of the site, there comes the challenge of how you realize it structurally.

Of course, during that stage, our internal team, local design institute teams, and consultant teams were involved in a rigorous process of designing the structural system. So, from a design point of view, how that would work, and how the building would stand up, and all the rest of it, and processing through the special review, structurally, to make the cantilever, and as well as the large span of working from design point of view, but that was just the first part of the story.

The more challenging one that came in later was during the construction stage, how you actually build it. Okay, in a way, the site is tight, and the building occupies pretty much almost all of the site. So, there was very limited access for the cranes coming to operate.

And also, the building, in a way, the project was affected by the COVID. In a way, there was a short period of being put on hold, which added massive pressure to the program in the timeline, so we still needed to catch up.

Then comes the third layer of the difficulty, looking at the span of the space right in the middle and what’s a better way to construct it. So for that, it’s a whole team effort, working together with the contractors, design consultants, and supervisors for a half-year kind of design study to look at the best way to construct that part of the building.

So the outcome of that was really to come up with this innovative idea of assembling the building parts on the ground and then hoisting them up into place by hydraulics. So, in principle, what it means is that I think we are talking about six bays of the structure assembled on the ground, so you don’t need a crane for that construction process.

Then, the weight was equivalent to about five jumbo jets. I think it’s 2,200 tons in total weight hoisted up. I think that was done in 13 hours or 14 hours, a relatively short period. About a meter or two per hour kind of speed, uplifting the whole chunk to 27 meters up in the air.

This method saved the need for a crane and welding, which you traditionally need to do on-site. It’s more accurate and then saves time and cost. It also worked with the site condition that we had, which was an amazing process. That was quite a ceremonial then, and then there was singing and dancing. Then, all the people came together because it was such an innovative approach; they usually don’t use that kind of technology for building and such.

Jinglu:

So is this the most challenging thing you’ve been through in the whole process, or what is the most memorable challenge you’ve met in the project?

Jeremy:

There were many moments during the construction, but let’s not forget that after we won the competition and started working with Alibaba directly, we were hit by COVID.

It was very challenging. We must all remember how challenging it was. It’s a challenging project. It’s a challenging design. After all, the delay was very costly, but COVID came, and we had to deal with it, even though we had never faced anything like this before.

So everything we planned for had to change. But I think we worked very closely. We frequently met on VC, and we luckily had our offices in Shanghai and Beijing. So, people from Shanghai, Beijing, and London, we carried on. It was a challenge, but remarkably well overcome. I think that’s another point that we wanted to make.

Jinglu:

You’ve mentioned Alibaba as a client, and was very supportive. I was wondering if there must be something that you raised in the proposal that was beyond the client’s expectation, right? Foster, as an advanced studio, you have all those great ideas. Is there anything that you proposed that went beyond the client’s expectations?

Jeremy:

Interestingly, the way I would put it, what I appreciate most about working with Alibaba is that they didn’t micromanage us.

They could have micromanaged us and told us to put a toilet here, make a public space there, remove the terraces, and put more. However, they didn’t. They didn’t give us a manual for designing the building. Instead, they gave us a vision.

They told us how they work. And what they want to achieve, but they didn’t tell us how they want to achieve it. And that’s the room so necessary for designers.

What you may call something the client didn’t give us or didn’t think of that we filled in. In a way, I disagree, respectfully. I think it’s necessary, and it’s so important that the client doesn’t tell us everything because that is micromanaging your designer.

That’s why we so appreciate how we worked with Alibaba. We completed this building together. Some parts came from the client, and other parts came from us. And, they’re not just us, obviously, as Foster Partners. There were contractors, there were other designers, and there were local teams.

Everyone who contributed to realizing this project. And, we all had our respective rooms, which were offered by Alibaba because they provisioned that room, you know, for us to think and offer and contribute. So again, it was a wonderful collaboration.

Yu Zheng:

There’s a level of trust before we collaborate. They trust and understand what Foster can deliver. We trust the desire of Alibaba, which wants to build an iconic, or let’s say, what they call it. A name card building that represents their identity worldwide.

Jinglu:

I think the trust also comes from your previous projects, So maybe I’ll have one last question. Jeremy and Zheng, do you have a favorite office building? It could be one designed by Foster and Partners or any other architects.

Jeremy:

I do. And surprise, it’s designed by Foster and Partners. But many years ago, I remember studying this building as a student and was blown away.

It’s called Willis Faber Building, and in a place called Ipswich in the UK. I think this building was the first open-plan office building in the UK. When Norman returned from the States after studying at Yale, he came across the idea of an open-plan office.

If you know the history of office buildings, an office started off as a space in people’s houses. There was no separate building where people worked. So the ground floor was where they worked, and upstairs was the bedroom, and so on. Now, naturally, the office, when the office came about as a concept, it was, there was a series of rooms, the office were never open plan, that didn’t exist. Then somebody in the States developed it as a prototype when somebody had an idea that it’s like a factory floor, wouldn’t it be great when people could have loads of desks, no walls, no rooms, we could fit more people into one big space. That’s fantastic. So that’s the birth of an open-plan office.

Now that was introduced by Norman to this country, and where he exercised and practiced that theory was the Willis Fable building in Ipswich. And that building is crazy in many ways. It has a swimming pool in the middle of the office. It introduced a roof garden, and that’s different because back then, the roof was for machines and services, and they still are. If you see buildings today, there are more buildings with roofs full of plants, ventilation machines, and so on than there are not.

I think Norman challenged everything through that project. And I don’t necessarily like that project because of the look of the building. I think the look is probably the least important factor, but it’s the ideas, it’s the way it challenges all the convention associated with office building is in that building. And that makes me, worship that building almost, I respect that building. I respect the idea behind that building. Yeah. So that. Still, to this day, it’s my favorite building.

It’s important because our job is not to design buildings, I think our job is also to innovate, and always question if there are better ways to do things. And Ipswich, the Willis Faber Building, did that very well. I think Alibaba Campus, in a way, did that very well. We could have just dwelled on conventional design, on the conventional way of designing office buildings, but we questioned and challenged, and we created something that is unique.

And by the sound of it, as you kindly said, it seems to be working. So that’s even more encouraging. Yeah. So that’s my little personal favorite.

Yu Zheng:

When it comes to me, I think, as boring as I am, not surprisingly, my favorite building so far is still designed by Foster.

I’m always impressed by the design that I did not expect. I think HSBC in Hong Kong ticked that box in a very amazing way. I think just two points I would like to mention is first was to integrate the idea of leaving the space or providing space back to the city. That’s probably one of those really early ones, I’m not saying probably the first one, but certainly early ones that the whole building was elevated up, leaving public spaces underneath. That was unseen before. That was really impressive. So that’s not a headquarters building standing on a piece of land in Hong Kong. As you would understand, how expensive an inch of land in Hong Kong would be. But back then, they decided to lift the whole building up and give that to the city.

Another view of life is the so-called high tech back then, but certainly, it’s not in a visual way. Still, it’s more of a functional way, i. e. the light reflector, getting the natural light deep down in the floor plate because they need to host so many people, the floor plate was quite big, however. There’s the introduction of the atria, as well as the light reflectors coming from the facade, bringing the natural light into the building, and so on and so forth, and how the building is structurally together to make that work.

Many years later, people still talk about the building as the first of its kind. For instance, making a panelized system. In a funny story I shared with different people, it was probably 20 years later that the building was designed and built. I was in one of those client meetings talking about panelized systems for ceilings and floors. And one of the consultants came out. He’s from Hong Kong. He asked if he knew who had designed this building. Who was the first one to design the panelized system for the ceiling? It was Forster’s. Reference back to the HSBC building in Hong Kong. That was the first time architects started to do that, and of course, many years later, everybody started to use that.

35 years passed, I can’t remember how many years passed, that building, if you look at it now, still looks super futuristic, does not belong to the time that it was designed and built at all, which is something over my imagination, in that sense, so I was indulged by that building by many factors. But to list a few.

Jinglu:

Thank you. I think the two projects you two mentioned both shared the value that design is not about just the building itself but about creating and innovating. And I think it also aligns with Alibaba’s corporate culture. So, I think it’s a very good way to end today’s interview.

Jeremy: Thank you very much for your time and for having us. And we also thank Selina for organizing this and inviting us. As we said, we’d love to continue working with Alibaba, and we’d love to go back and see how our building is doing.

We’re so honored and privileged to have been involved in this amazing project. Thank you very much.

Yu Zheng:

Thank you both.